Gratitude and Redemption Thanksgiving Reflections

by Fr. Frederick Edlefsen

When Giovanni da Verrazzano explored North America’s eastern seaboard in 1524, on behalf of King Francis I of France, he sailed from what is now North Carolina through New York Bay and Narragansett Bay up to New Brunswick. He named Virginia and Maryland “Arcadia” because of the land’s lush and verdant beauty. The name “Arcadia” was later given to Canada. As a side note, Samuel de Champlain, the 17th century father of New France, dropped the “r” from Arcadia, thus calling French Canada “Acadia” or “Acadie.”

Verrazzano’s excursions along the east coast were tangential at best, and he didn’t have time for studious observations and mapmaking. Some of his surmises were wrong. When he reached what is now Pamlico Sound, North Carolina, he thought he found a passage to the Pacific Ocean and a route to China. However, his intuitions in naming the land “Arcadia” were perceptive. He couldn’t have known that this tidal seaboard and the inland piedmont comprised one of the most arable, habitable, beautiful and ecologically complex places in the world. Nor could he have known about the spectacular, wooded and mineral rich mountains – among the oldest in the world – that lie farther inland. His naming it “Arcadia” was but a first impression. Was it lost Eden? Had he discovered the Paradise from which Adam and Eve were expelled? Or some remnant of it? Or something like it? Could this discovery be mankind’s second lease on life? A second shot at Paradise on Earth? Did the Fountain of Youth flow somewhere in those beauteous woodlands? These were, in fact, fashionable curiosities during the so-called Renaissance.

To Verrazzano, the virgin lands must have suggested an ancient Greek ideal of perfect “pastoral” life in harmony with nature, a bucolic garden inhabited by sheep and shepherds. This ideal still looms large in some veins of the American psyche. “Ah yes! A serene country life! Let’s retire to Vermont!” “Keep Ashville Weird.” “We bought a farmhouse on the Chattahoochee.” The great American landscape painters of the 19th century, known as the Hudson River School, founded by Thomas Cole, colorfully illustrated this idyllic vision. For example, there is Cole’s painting “The Arcadian Pastoral State” (1834), which is the second picture in a five-part series known as “The Course of Empire.” Cole also painted “A Dream of Arcadia” (1838). “To the Americans of his generation whose imaginations were stirred by the continental vastness of the new country, its unscaled peaks and trackless wilderness, its beauty and its promise, Cole’s pictures provide the pictorial ideal” (Perry Rathbone, Bulletin of the City Art Museum of St. Louis, 1946). Verrazzano’s Arcadian impressions of this land would echo through the noblest strands of North American art, literature, music, politics and culture for centuries – and they still do.

When Europeans first encountered this “Arcadia,” the land was heavily populated by peoples now called Native Americans or Indians or, in Canada, First Nations. Some areas of the continent may have been more densely populated than the great population centers in Europe. Native civilizations were often culturally thriving, with refined systems of politics, diplomacy, agriculture, hunting, trade, war making, sports, art and religion. All told, the North American continent provided homelands for over 500 distinct tribes speaking over 300 languages, with a remarkable cultural diversity. These peoples gave us corn, beans, squash, tomatoes, potatoes, chilies, chocolate, vanilla and tobacco. By the time the first English settlers arrived in Massachusetts in 1620, most of the Native population in the southeast had been decimated by plagues unwittingly brought from Europe by Hernando de Soto’s entourage and his Iberian pigs – progenitors of Arkansas razorbacks – in 1539.

Meanwhile, in the northeast, Iroquois and Algonquin speaking tribes cultivated corn, beans and squash in integrated fields. These natives grew prolific bean vines on cornstalks, which shaded patches of squash below. This ingenious farming technique created a natural balance of fertility, sun, shade and moisture. Food yields were markedly higher than those produced by European farmers in North America and in Europe. It was sustainable farming. This might be the real providential blessing behind our Thanksgiving legend.

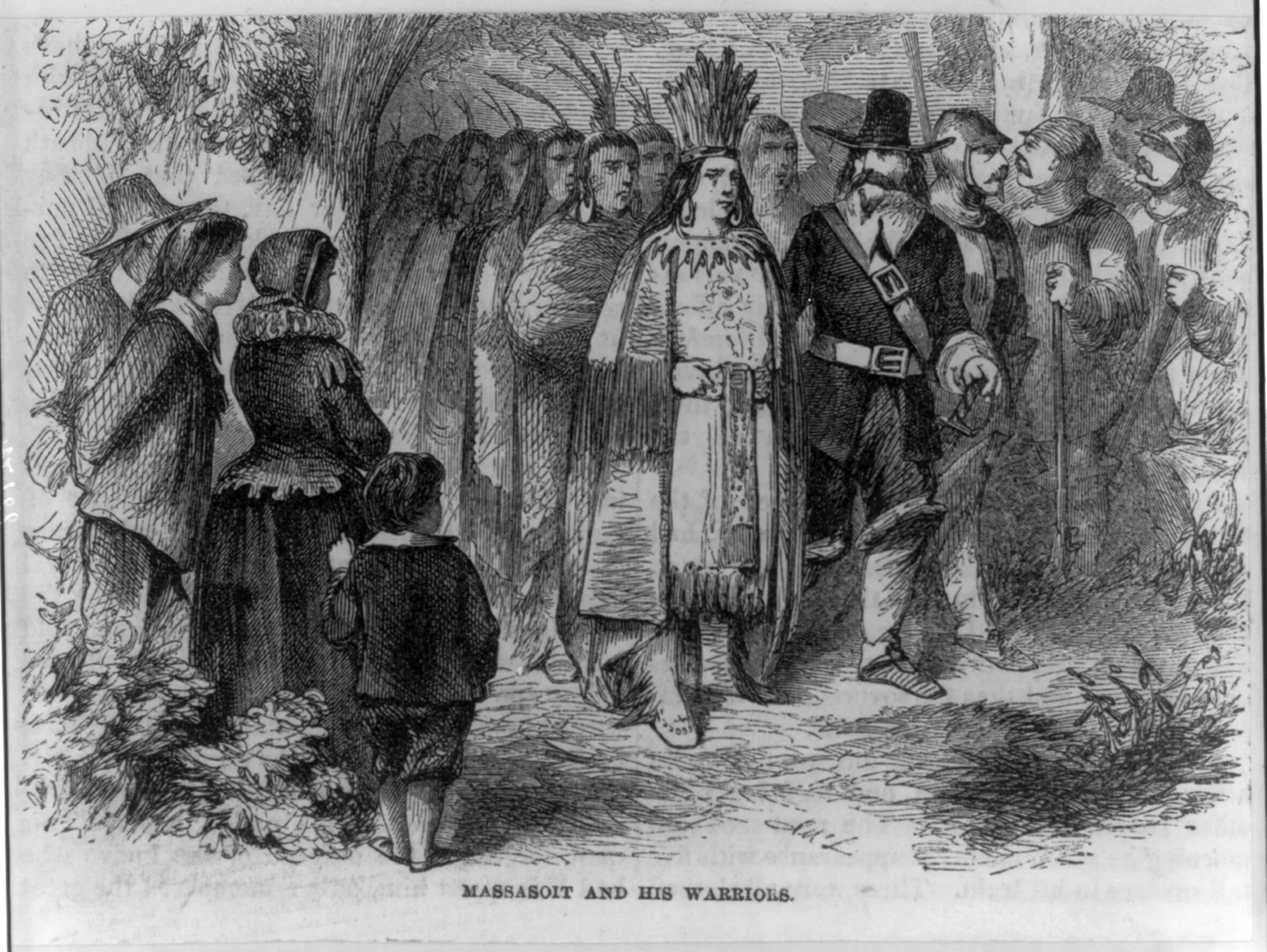

In the 1620s, Chief Massasoit of the Wampanoag, an Algonquin speaking tribe in what is now Massachusetts and Rhode Island, was perhaps the most important player in the success of the Plymouth Colony. He was from Pokanoket village, in today’s Rhode Island, which had been devastated by plagues brought by the settlers. His support and alliance with the English was, for him, a shield against the more powerful Narragansett to the south. Massasoit was a man of his word, evenhanded, prudent and peaceable. A colleague of questionable loyalty, known as Squanto (or Tisquantum) from a Wampanoag band called Patuxet near Plymouth, was living with Chief Massasoit when the English arrived. Squanto had a painfully dramatic history with English adventurers before the Mayflower’s arrival, but that’s another story. Suffice it to say, he was a liaison between the Puritan settlers and the Wampanoag. Under Massasoit’s and Squanto’s leadership, the Wampanoag taught the Puritans how to rotate crops for soil fertility and yield. These lessons in sustainable farming and “how to survive winter,” rather than an actual feast, are the known historical facts behind our Thanksgiving narrative. Despite the lack of evidence, there may have been a feast – but who knows?

Some historians believe that the historical basis for Thanksgiving dinner was a feast that took place after the Pequot War (1636-1638). That war was a tragic conflict between the Pequot tribe and an alliance of Mohegan, Narragansett and English colonists. The Wampanoag were neutral. In the war, the English shamefully massacred a fortified Pequot village along the Mystic River in Connecticut. The village was set ablaze, with inhabitants trapped within its palisades. Able-bodied escapees were shot. Trapped women, children, infirm and elderly were burned to death. It was arguably genocide. Even the Narragansett, enemies of the Pequot, were repulsed by the brutality. Prisoners were either sold into Caribbean slavery or sent into captivity elsewhere. Nonetheless, Massasoit preserved Wampanoag neutrality. Perhaps the actual “thanksgiving” feast was a gesture of peace or solidarity with the English after the war? Again, who knows?

Wampanoag-English relations declined after Massasoit’s death in early 1660s. The ensuing drama was complex and dirty, and the details are sketchy. Massasoit’s son, Wamsutta (Alexander), allegedly died of poisoning, though this is not proven, after his first altercation with the English. Things got worse when the English falsely accused three Wampanoag of murder and hanged them. Wamsutta’s surviving brother, Metacom (King Philip) forged a confederation of local tribes against the English. Gruesome hostilities ensued, mostly in Connecticut, for three years in what is known as King Philip’s War (1675-1678). The Wampanoag, a tribe of less than 1000, were reduced to about 400. About ninety English settlements were either burned or severely damages. The English killed Metacom and displayed his head on a pike near Plymouth for over twenty years. His wife and children were sold into slavery.

Out of the smoke of these dark events arose a legendized holiday known as Thanksgiving. Some Native Americans and others see it as a “day of mourning.” How should we read history? It’s the tragic tale of Cain and Abel continued. It’s an episode in the ongoing battle between Dark and Light that will end in the Final Judgment.

Despite our sinful cruelty, the very idea of Thanksgiving suggests that noble sentiments like Gratitude are not lost on our conscience. Sin wounds and destroys, but not definitively. There may well be something narcotic about the quaint and comic legend of Pilgrims in capotains and Indians in feathered headbands, fellowshipping over turkey and squash. Thanksgiving may well be a celebration of what we should have done rather than a celebration of what we did. Like wishful dreams about Arcadia, Thanksgiving may be a celebration of a Gratitude that “should have been” in an event “we wish had turned out differently.” “If we could do it over again….” If only the players in the game had “eyes to see” (Mark 8:18).

See what? Gratitude: A form of Justice rooted in Humility. It could have given the world an historical case-in-point of a goodness that mankind is capable of, with grace. But for reason to be revealed at the Last Judgment, it was not foreseen by Providence. But the Thanksgiving tradition was. The legend may be a spark of “hope for redemption” that still smolders beneath the ashes of sin. In truth, only a Resurrection of the Dead can render Justice for some crimes. A feast idealizing Gratitude perhaps indicates a desire for that Justice which resolves history. Moreover, it suggests that we can do things differently, now. “Give us this day our daily bread.”

Verrazzano did not discover Arcadia. The Puritan ideal did not happen. “We shall be as a city upon a hill….”, said John Winthrop. Only Christian feasts, from which the Puritans wanted to “purify” the Anglican Church, are rooted in innocence: feasts of Jesus and Mary who were always innocent, and Saints who were made innocent by grace. Grace brings Light from Dark. It can do the same for Thanksgiving. We need not be afraid to expose the Darkness to the Light and admit that our forebears were not always noble and just. Nor are we. We are not above the sins of our ancestors. “If I was there, I would not have...” You probably would have. A future generation will condemn our blindness some day. In the meantime, Thanksgiving should occasion Gratitude for what we have received and Penance for we’ve done. Gratitude heals. Above all, we ought thank God our Father who, through the sacrifice of his Son, makes this possible.

*I am indebted to Dr. Anton Treuer’s “Atlas of Indian Nations” for many of the facts about First Nations contained in this article. Mistakes are mine.